Macronutrients For Endurance Training

Endurance training and running is experiencing a bit of a boom at the minute! Gone are the days of every gym bro just trying to max out their bench press and be fit enough to walk to the gym and back, we’re currently in the era of the HYBRID athlete. With a change in training style comes a change in fuelling too, so here we’re going to dive into fuelling for endurance.

We will look at the physiological determinants of success in endurance training and how training brings about improvements in these factors before then diving into how to manipulate your macronutrients to marry the training. We’ll look at being as efficient as you can with your macros and fuelling the work required.

Let’s dive in.

3 Limiters to Endurance Performance

First things first, when looking to improve your endurance performance what is it that you’re actually looking to change?! Looking from the top down, the things we’re striving for are essentially the ability to delay the onset of fatigue at varying exercise intensities. To be able to go for longer at lower intensities and for the baseline intensity to be higher across the board right?! We want to be moving faster for longer. Over the years there have been several papers looking at the determinants of endurance performance and they all essentially come back to 3 factors!

Your aerobic performance (measured by your Vo2 Max and lactate threshold)

Your anaerobic performance (measured by time spent above the lactate threshold)

Your mechanical efficiency which can manifest itself as running economy or cycling economy.

Here’s a fantastic flow chart taken from Joyner and Coyle’s (2008) “Endurance Exercise Performance: The Physiology of Champions” showing how those 3 factors are linked to overall performance and the underlying physiology of our bodies.

But why do it?!

As we can see from this, the line of determinants at the bottom are the things that we can influence (well some of them) in our physiology through training and nutrition to improve our overall performance. Endurance training itself is found to improve these on its own but nutrition can be manipulated to amplify those adaptations even more.

Before we dive into specific macronutrients and make changes to those. It’s first important to touch upon that all important aspect of energy balance. Because yes, it still matters. Being in a caloric surplus or deficit will affect some of these physiological markers, the most common example in endurance work is perhaps being in a controlled caloric deficit to reduce fat mass to improve mechanical efficiency. This is of course useful for improving performance, but being in a prolonged caloric deficit around competition is NOT going to improve performance as energy availability will be low. It’ll be important to periodise when you carry out these changes, something we will touch upon later on.

For now, though I believe it’s worth highlighting the energy cost of endurance training, as it is often underestimated. In 2017, Heydenreich et al carried out a systematic review looking at energy expenditure, intake and body composition of endurance athletes across their training season. The results for energy intake and expenditure are shown below.

We can clearly see that energy expenditure is dramatically more around certain times of the year, again we’ll touch on this later. But we can also see that for the most part, energy expenditure seems to be more than energy intake for both males and females across the training season.

Obviously, this is not going to be the case for everyone as those with proper nutrition planning will counter this, I believe it’s just worth noting the larger energy cost of exercise as it’s often underestimated and can thus lead to symptoms of RED-S.

Protein

Ok, so we’re aware of the energy need for endurance sports. Now to look at where we should get this energy from to be efficient with our nutrition and bring about the physiological changes we want. Let’s start with everyone’s favourite macronutrient as it’s perhaps one of the simplest to deal with from an endurance point of view.

I am of course meaning PROTEIN. Here we want to think about mechanical efficiency, we don’t necessarily want to be increasing muscle mass, more just improving the strength and endurance of the muscle we have. SO do we need to eat as if we were stimulating hypertrophy? Probably not. Let’s use me as an example here.

Here we have two pictures of me. On the left I am sitting at 75kgs and my goals with training are to increase muscle mass and strength. I was consuming around 2g of protein per kg body weight per day and spacing it out across my day in servings of around 30g of protein per meal. These are common recommendations for maximal muscle protein synthesis and they seemed to work for me (who knew ay). There is some emerging evidence on more (potentially up to 4g/kg BW per day) being beneficial but for me, this target worked.

On the right, I am running the Sheffield half marathon and weigh 5kgs less. I'm short and stocky, built like a hobbit on creatine, i.e. not for running. But I still wanted to tailor my nutrition to suit my goals. I knew that I had to alter my mechanical efficiency and maximise my efficiency of fuel usage! SO protein took a hit, I took it down to around 1.6g per kg body weight to maintain some of the muscle mass I had but to also make room for more carbohydrates and fats. I was not looking to build muscle, just maintain what I had and could even potentially have gone lower!

Recommendations of around 1.2-1.6g per kg BW for endurance training are a great starting point.

But as with everything It’s relatively fluid and can change dependent on the more individualised goals and needs of the athlete. It’s also worth noting that if you are planning a fat loss phase to improve mechanical efficiency then more protein might not be a bad thing! This is why the fluidity of targets is key, they should match your goals at that point in time.

Carbohydrates and Fats

Let’s move on to carbs and fats. We’ve lumped these together as the manipulation of them will be KEY in bringing about the physiological changes we want such as aerobic enzyme activity.

In recent years there has been an incredible surge in the amount of research going into ketogenic diets and endurance performance. One of the driving theories behind this research is that we can essentially store more energy in the form of fat than we can in the form of carbohydrates.

Our body can store around 600g of glycogen, this equates to about 2400kcals worth of energy. Fat stores on the other hand are larger, and fat itself packs more of an energy punch. Let’s use some maths for context, imagine a lean 70kg man with 10% body fat, they have 7kgs of fat on their body!

Obviously, some of this is essential for our bodies to survive, but for the sake of this, let’s say it isn’t. 7kgs of fat is around 63000kcals. Thinking back to our energy expenditure table, this is enough to fuel multiple days of training even in the competition phase.

So if we can access these stores of fuel surely fat is going to be our best source of energy for endurance work?! Let’s look at this from perhaps the most extreme example of “fat adaptation”, the ketogenic diet.

There are many supporters of the ketogenic diet in both the general population and the academic world, the notorious Tim Noakes is just one of these. Because of this support and the potential benefits of accessing our fat stores to fuel us, there has been a large amount of research into the ketogenic diet and endurance performance. In 2019, Dr Fionn McSwiney wrote a review article on just this.

He found that ultimately the ketogenic diet offered no significant advantage to athletes across any kind of intensity or time domain. Most studies showed that although there was no decrement in performance for low to moderate intensities, there was also no benefit from going keto.

However at the top end of the intensity scale it seems that decreased power output and thus performance occurs when people have followed the ketogenic diet.

This makes sense as at those high intensities anaerobic metabolism dominates, of which glucose and glycogen are our bodies preferred fuel source. So it seems that going keto offers no benefit for performance and can even lead to you losing that 5th gear! Carbs are most definitely still kind for the most part.

Here is a great image from Asker Jeukendrup supporting these findings from other research studies.

Training low

Although the ketogenic diet offers no discernible benefit and carbs are still king for competition performance, there may be a way that we can use fats to our advantage. If we can increase our bodies metabolic flexibility so that it uses fats at low intensities when plenty of oxygen is present and then spare our carbohydrate stores for when we really need them then this may improve our capacity. This is an idea that has been taken into practice via the Train Low Compete High principle.

The train low compete high principle is exactly what it says on the tin! Carry out some periods/sessions of endurance training in a state of low glycogen availability but compete in a state where carb stores and energy availability is HIGH!

In this way metabolic flexibility can be achieved and the benefits of carbs still used.

Personally, I don’t believe that training low across the entirety of the training year or season is a good idea. I believe that it should be periodised both week to week and across the season.

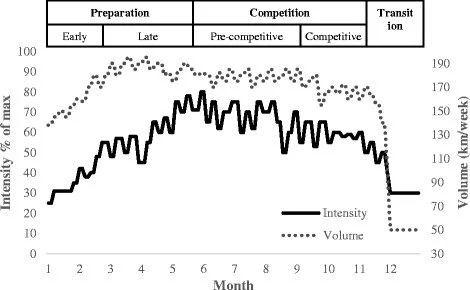

Let’s put this into context using another graph from Heydenreich et al’s 2017 paper on endurance athletes energy expenditure.

This graph lays out the changes in intensity and volume in an athletes training across the season.

As you can see in the competition phases, intensity is higher than in early preparation. To me, this says early preparation phases are a fantastic time to incorporate some training low into your routine. The intensity won’t be high and so in terms of dominant fuel sources, you won’t be as dependent on glycogen and carbs.

You can lay the groundwork for metabolic flexibility and carb sparing in the early stages before increasing carbs as intensity increases across the season.

You can also look to periodise like this within the week with some micro periodisation. This would essentially look like adaptive and performance sessions. I.e some sessions whereby you train low and work to improve fat oxidation but the performance of the session may suffer (adaptive) vs other sessions in the week that you go in well fuelled for, ready to perform!

Not every session will need to be adaptive and if every session is a performance session you’re bound to miss out on adaptation. This paper explains this concept in a little more detail regarding carbohydrate availibility.

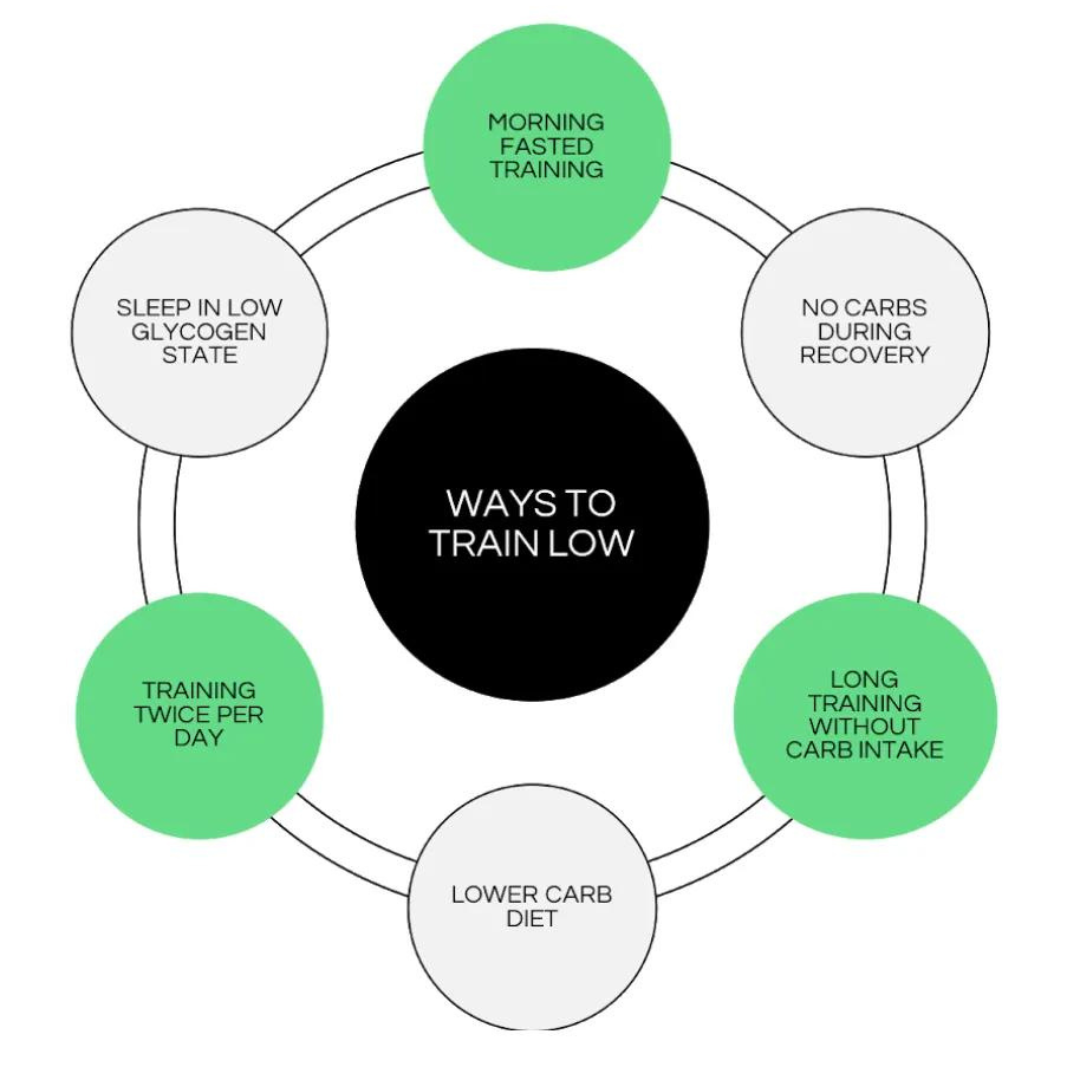

Having established that training low and periodising your macros around this may improve your endurance performance, here’s a diagram detailing ways to train low.

Optimal isn't practical

If you read some of the research on carbohydrate intake and endurance training, the numbers may scare you a little!

As you can see from the table below, it is widely reported that 5-12g/kg.bw of carbs is needed when performing regular endurance training.

That is 350g of carbs per day for 70kg person if they are doing around 90 minutes a day training. In my opinion, this is ALOT for daily training away from a competition set up.

Getting up towards 700g per day is simply unachievable for almost all of us.

This is why I say OPTIMAL IS NOT ALWAYS PRACTICAL

As I have covered in the previous sections, you need to manipulate carb intake to elicit the correct adaptations to the training you are doing. Carbs are key for performance, but more is not always better.

Putting it all together

We’ve covered protein carbs and fats but now let’s put them all together! We’ll use myself as an example for context and to get some numbers down, but before that we want to attack a framework for periodising your nutrition. This is a framework laid out by Trent Stellingwerff et al in a 2019 paper and it follows a flowchart of decisions based all around the determinants of success!

Let’s put this framework into practise using what we know about macros for endurance and limiting factors.

Let's use myself as an example! I am 5ft7, and weigh around 75kgs and not a natural-born runner. Let’s say I want to run a marathon, I set a date in let’s say 3 months and get training. Initially, because of my frame, one major gap for me will be mechanical efficiency, so I’ll plot out a phase that involves some fat loss to ensure I lean out a little and mechanical efficiency can improve! This will be in the early stages of my training so the intensity will still be relatively low.

I’ll be in a caloric deficit (which for me is anything less than 3000kcals at the minute based on an RMR test) and I’ll attack some low and slow work so my carb intake may be reduced, I’ll keep my protein intake relatively high to encourage fat loss as opposed to loss of lean mass. My macros would look a little something like this:

Energy, 2500kcals/day

Protein, 150g/day (2g/kg BW)

Carbs, 250g/day (around 40% of total energy contribution)

Fats, 100g/day

I’d also periodise my carbs depending on the type of session I would be attacking. I’d incorporate fasted training into this early stage and most sessions would be lower intensity. After around 4 weeks of leaning out, my mechanical efficiency would (theoretically) have changed. It would be time to head back to the flow chart and attack a new determinant of success!

In the early training phase, I'd still be working to improve aerobic power, metabolic flexibility and just generally building my base! I’d take my intake up to maintenance and keep protein still relatively high in this early phase still, I would then essentially just bring carbs and fats up in the same proportion to keep the ratio the same.

Then as the intensity and volume of training started to increase, I’d enter the comp phase! I’d want energy availability to be high SO protein intake would reduce to around 1.2-1.6g/kg BW, (the higher limit for me as I’m habitually used to getting so much in) carbs would then increase to fuel this high-intensity training and get me ready for the higher amount of carbs I’ll be eating before and during an event! Fat would take a little hit and my macros might start to look a little like this.

Energy, 2800kcals

Protein, 120g/day

Carbs, 400g/day

Fats, 80g/day

As you can see this is a fairly carb dominated diet and it’s important to note the context for this would be around the competition phase of preparation for an endurance event, not for daily life!

Let’s finish with some key takeaways

Try to periodise your nutrition to align with your training. Manipulating overall calories, protein, carbs, fats and the timing of these will help elicit the correct adaptations

Protein is crucial for endurance athletes. If you are in a deficit or doing more strength training to build muscle, the aim for 1.6-1.8g/kg/bw. When doing higher volume training or leading into an event, reduce to around 1.2-1.6g/kg.bw.

Carbohydrates are crucial for optimal performance. Aim for around 40% of total caloric intake and then increase this when the volume of training increases. Unless you are an elite athlete aiming for around 4-6g/kg/bw is advised in this stage.

Manipulate carbohydrate intake to help enhance specific physiological adaptations away from competition.

Fats should be on a see saw with carbs. As carbs go up, fats come down and vice versa.

So there we have it, a deep dive into macronutrients for endurance training. We’ve covered the what, the why and the when around protein carbs and fats and endurance. It’s been one hell of a ride but it’s important to note that this is ultimately just the starting point! When it comes to nutrition and endurance there is still more you can attack, things like hydration, key micronutrients, what to do in comp week, carb loading and so much more.

I’ll be diving deeper into these over the coming months but for now, sink your teeth into some serious endurance work and some serious carbs!